Conscious experience has been described by numerous philosophers over the ages. For instance, Aristotle regards conscious experience as a representation composed of images, Descartes(1641) describes conscious experience as things laid out in space and time, Dennett(1991) describes a person viewing events in a “plenum” (a material space), and so on. In general conscious experience is described as things within the view of an observer that are laid out in space and time. These descriptions can be agreed by all of us as we look around and sense the world and our bodies.

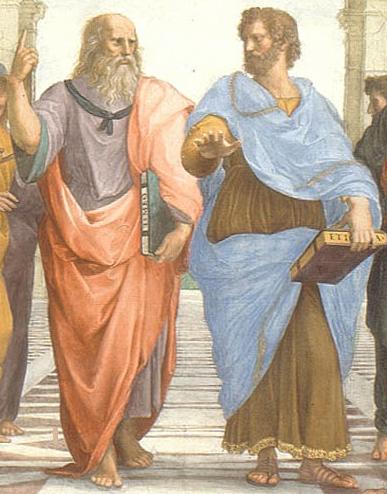

Plato and Aristotle by RaphaelCourtesy Wikimedia Commons

Most people would agree with the general description and even place verbal thoughts “in their head” (Ryle 1949). How this experience becomes “conscious” is generally regarded as a mystery but the experience itself also has mysterious qualities. The most mysterious quality of experience is how a simultaneous and continuous set of things that are distributed in space can become part of a “view” in which they appear to be arranged around an observation point. We seem to look out at the world as if seeing it from a point eye and even our dreams and imaginings appear as if seen from an inner eye. How can we explain this? Is conscious experience an illusion and simply an inference produced by the processing engine of the brain or is it a physical phenomenon in its own right? If it is a physical phenomenon then what is its physical description?

A note on naïve realism

"There is no point eye that receives a conical view of the world"

Before proceeding further I should consider a couple of misconceptions about geometrical optics. The first misconception is that there are images out there in the world. Images are properties of optical instruments and the reason that paper is white is that the light that falls on it is disorganised and comes from everywhere around: photons go all over the place and do not make images outside of instruments. The second misconception is the belief that our eyes act as a single point that sees the world projected around it. There is no “point eye” that receives a conical view of the world, the reality is that light falls all over the cornea to be redirected to the retina. It is also the case that when I wink about thirty percent of the visual field is blanked out, I have two eyes with sometimes quite different images in each and only one conscious, visual experience so the idea of a physical “point eye” looking out at a cone of light rays does not correspond with the physical facts.

Images are different in the two eyes Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Aristotle's analysis

"..if we have experience then the impressions that are the source of this experience cannot endlessly give rise to further impressions; somewhere the chain of impressions stops and something other than transferring impressions occurs to make experience."

Aristotle, some two and a half millennia ago appears to have understood that we could not explain conscious experience through optical considerations alone. In his book, “On the Soul”, he notes that information travels from the world to the eye by making “impressions” on the materials that intervene between the object of vision and the eye (1). He also spots that successions of impressions could never lead to our visual experience because the simple transfer of impressions from place to place would lead to an infinite regress (2). Aristotle responds to this problem by proposing that the transfer of impressions must end somewhere so that “in every case the mind which is actively thinking is the objects which it thinks.” (3).

In other words, according to Aristotle, if we have experience then the impressions that are the source of this experience cannot endlessly give rise to further impressions; somewhere the chain of impressions stops and something other than transferring impressions occurs to make experience.

The alternative to Aristotle's view is to deny much of conscious experience and to maintain that there are only judgments about the world (Dennett 1988). This approach allows the neuroscientist to investigate reflexes and behavioural responses but it may be avoiding the issue of the nature of experience itself. The problem of whether or not we fool ourselves with incorrect judgments about conscious experience will be considered after describing this experience.

Describing conscious experience

"..When I look in a mirror I cannot observe my eyes moving even when I deliberately move them to left and right,.."

A description of conscious experience is needed before I can address the problem of the nature of conscious experience.

As a simple beginning, suppose that I limit my description to visual experience obtained using one eye. This provides me with a limited view of the surroundings with a small segment of my nose on one side and little sense of depth. Several things can persist in my view over a period of time and so I say that I have things simultaneously in my view. I describe the way that there is more than one thing present at any instant by using the word “space”, for instance I say that these two letters "ii" occupy space. My view is clearest in a small, central zone. The relative lateral separation of the elements of the view from the central zone depends, approximately, upon the angle that they make at a point that coincides with the one eye. The elements of the view also compose what I call a “surface” because only one side of anything is in the view.

If I hold the shaft of a pin or paper clip immediately in front of the one eye then I can see right through it. This demonstrates how the image in the view is formed from light that falls all over the cornea of the one eye. The shaft would obscure any "point eye".

When I look at the world using two eyes instead of one the view scarcely changes but the side of my nose disappears and the view expands by about a third. The point at which things are directed is like a centre of the possible visual field. This description of a viewing point corresponds to the descriptions given by Reid(1764), Descartes(1664) and Leibniz(1695).

If I place a finger in front of the centre of one of my two eyes it seems as if I can see straight through the finger, although a semi-transparent outline of the finger remains. If I gently press the side of one eye through the eyelid the view becomes a double image. These effects demonstrate how the images from both eyes are combined to form a single image.

When I look in a mirror I cannot observe my eyes moving even when I deliberately move them to left and right, looking from one eye to another. This “saccadic suppression” suggests that what I am observing may not be the images that are on the back of my eyes but an image in my brain. If I rotate my whole body as rapidly as possible to simulate eye movement without saccadic suppression then the moving retinal image is not suppressed and I can see that without saccadic suppression and the creation of a stable, internal model, my view of the world would be a useless blur. (This actual observation is the opposite of Blackmore's (Blackmore 2002) inferred conclusion that there is no visual content between saccades, as are the red dots that appear during saccades across modern, pulsed, LED rear car lights at night).

Over longer periods my experience also seems to involve what I call “time” in the form of continuity and change. Philosophers such as Aristotle, Descartes(1641), Kant(1781), Clay(1890), James(1890) and Whitehead(1920) have all noted that experience seems to contain a whole interval of time, a “specious”, “psychological” or extended present moment. But what is the extension in time within experience like? Clay(1890) observes that we hear all the notes of a bar of a tune as a single segment of time and Gombrich(1964) writes that we do not just hear a single phoneme of a word but hear the whole word spread through time. The essential feature of these reports is that experience seems to be arranged along an independent time axis with the various events, such as the phonemes of a word, being separated along this axis. I also find that words, bars of tunes etc. appear to be extended through about a second of time but experienced now. (The way that two separate times can be present now is explained below).

I notice that the existence of time within my experience also allows me to have “directions” within it. If I drop a small object a short distance then the motion occurs inside my experience and it is a whole sweep of experience that lasts through the time taken. The motion is from the start point to the end point and so has a direction.

Time also seems to affect the view within my experience, for instance, if I change visual focus from a nearby to a distant object then the change of visual content occurs within my extended present. I call this possibility of motion away from my viewing point “depth”. This description of depth corresponds with Cutting and Vishton's (1995) idea of “action space” and means that what I call spatial separation in directions along a line from the apparent observation point away from me is actually a possibility of temporal separation that can be made active by movement into it or imagining a movement into it.

The existence of directions within my experience can be used to describe the surfaces that occur all around me as surface elements that are directed towards my viewing point.

When I listen to music on a “Hi Fi” with one loudspeaker the sounds come from the direction of the loudspeaker. Each bar of music comes from the direction of the loudspeaker but the start of each bar is prior to the end of each bar at that position. I find that as the elements of music move into the past they appear to continue to be directed at a listening point in the present instant. This allows a segment of the past to be in my experience now.

I will give an example of how a segment of the past can be in my experience now. When I see someone speaking the sound seems to occur at the same place as the sight of their mouth. Each phoneme forms auditory elements at the mouth that are directed at my apparent listening point. As “time passes” the phonemes are not lost. I do not just hear the “o” of “hello” but hear the whole word and still have the “he” in experience. The word forms an arrangement of directed elements, the phonemes, extended through time at the position of the mouth of the speaker, each element being directed at a common point, the centre of my experience, in my instantaneous present. The elements that compose the word are terminated abruptly at the end of the word.

The time extension of my experience is similar to the spatial extension of my experience. Spatial extension involves the angular separation of elements at a point and time extension involves the angular separation of events in the past that are directed at the point of my present instant. This description of the extended or “specious” present agrees with William James' (1890) description: “In short, the practically cognized present is no knife-edge, but a saddle-back, with a certain breadth of its own on which we sit perched, and from which we look in two directions into time. The unit of composition of our perception of time is a duration, with a bow and a stern, as it were -- a rearward -- and a forward-looking end.”.

The time extended sets of events in my experience always have the direction earlier to later. Despite this directedness of events I feel as if I am "now". If I am "now" then why do not events appear as if they are directed from the present into the past? They do not appear directed from the present into the past because they are separate from the apparent observation point. As in William James' analogy of a "saddle-back", I experience events laid out at a distance and directed from past to present but viewed as if from the point of the present instant of my viewing point. Like James, my "now" seems a bit behind the leading edge of events, for example, if I hear a pigeon cooing my listening point seems to be between the two repeated "coos", with the second ahead of it in time and the first slightly behind it although both "coos" are in my experience. As experience progresses my listening point moves along the time axis with the sounds.

I mentioned earlier that experience terminates abruptly at the end of a whole word. When my apparent listening point draws level in time with the end of a word it ceases to be in my experience unless I actively recall it. It is as if whole, time extended words are mounted in my experience at the location of the speaker and then the relation between the listening point and the time extension of the word is such that the listening point travels from the start of the word to its end.

All parts of my experience, whether thoughts, imaginings, touch, taste or sight etc. occur over a period of time. To say that something occurred for no time at all would be equivalent to saying that it did not occur.

I also cannot find any experiences that do not have a spatial component and disagree with Descartes(1641), who writes that thoughts have no spatial extension; my thoughts are in the position of my head and have a rather nebulous position within it. Sometimes inner speech seems to come from near my vocal chords and mouth, sometimes from around the back of my head and sometimes from between my ears. But wherever my thoughts reside they have a spatial location. I also disagree with Clarke(1995) that some thoughts are non-spatial, especially during meditation. When I perform an Eastern style of meditation I am left with space, not no space at all. If I allow the meditation to expand then my experience is a boundless space and if I perform the meditation in the Taoist style, with eyes turned slightly inwards, I experience a continuum of light as the space rather than relative darkness. The various sources on meditation agree with my experience, for instance standard Theravada Buddhist texts describe advanced meditation as modulations of the state of boundless space (Gunaratana 1988). However, even if Clarke has a private meditational experience that disappears as a content-less geometric point he still describes his perceptual experience as spatial.

Although I cannot find any non-spatial parts of conscious experience I can find things in my experience that seem to come from processes that are outside of my experience. For instance words occur but nowhere in experience is there the action of putting together the phonemes of the word, I engage in movement but the muscles have their own instructions that are outside of my experience and so on.

The apparent paradox of two times being simultaneously present

"..different times can in principle subtend an angle at a separate point in space and time in the same way as different positions in space can subtend an angle at a separate point in space."

The description and analysis given above treats the extended present as real and this idea of a real, extended, present moment has been attacked by numerous philosophers on the basis that, by the definition of the word “simultaneous”, events at two separate times cannot be simultaneous (Le Poidevin 2000). However my actual experience is having events at two times that are directed at a common point elsewhere. If time is an existent direction for arranging things and space-time exists then different times can in principle subtend an angle at a separate point in space and time in the same way as different positions in space can subtend an angle at a separate point in space. This idea of the extended present as a segment of a real, existent time dimension is consistent with “four dimensionalism” (Rea 2003) and also consistent with the recent experimental demonstration of the existence of physical time (Lindner et al 2005).

The passive nature of conscious experience and the function of conscious experience

"..it is impossible for an idea to do anything, or, strictly speaking, to be the cause of anything."

I noted above that words and motions occur in my experience without the detailed construction of these words or motions being evident. My own actions and thoughts all seem to be historical in the sense that they appear fully formed and in the past. When I say "now!" the "now" is always past and fully formed, I do not have an "n" in my experience and then undergo a dialogue about whether to put an "o" afterwards to make the word "now". Berkeley noticed this aspect of experience: "A little attention will discover to us that the very being of an idea implies passiveness and inertness in it, insomuch that it is impossible for an idea to do anything, or, strictly speaking, to be the cause of anything.."(Berkeley 1710).

The passive nature of conscious experience is not surprising because it occupies a small segment of the past and action occurs now.

My conscious experience is where thoughts and sensations are displayed, not where they are mechanically created. It is possible that my conscious experience is in some way involved in the selection or creation of thoughts but this would occur at the boundary between the future and the past and I have no insight into instantaneous events. When I am unconscious I do nothing but when I am undergoing conscious experience I can perform actions so my conscious experience is permissive of, or enables, action but it does not directly cause what is classically known as "action".

A consequence of Berkeley's observation of the passive nature of conscious experience is that what we call "conscious" actions must be non-conscious and due to activity in non-conscious parts of the brain. In confirmation of this prediction a delay between the first neural indication of a conscious action and the appearance of intention in conscious experience has been shown by Kornhuber and Deecke (1964), Soon et al (2008) etc. This delay is known as the "readiness potential". The delay varies between 0.2 and 7 seconds. These results confirm that attempts to use functionalism to explain experience are a category mistake (See Ryle 1949), conscious experience is not a set of actions, it cannot generate classical actions and cannot be explained by processes alone.

An analysis of the description

I have described the existence of geometrical elements such as independent directions (dimensions) and directed elements within my experience but what of this peculiar, “apparent” observation point?

The elements that are directed at the apparent observation point have characteristics such as orientation towards the point (one sidedness) and angular separation at the point that are properties of something that has a direction. I have already mentioned the way that “depth” is due to a potential for movement towards or away from the centre of the view within experience so it is possible that the things within my experience, such as the surface containing this writing, have a direction along the time axis towards the centre of my experience. However, although they are directed towards a viewing point these things cannot actually move into the point because they would become scrambled up together and many things cannot coexist in a 3D geometrical point.

So there is a conundrum: how can something be at a point but also arranged in space and time? If a movement through space into a point is forbidden because many material things cannot be at a point then the alternative is that the net separation between the point and the elements of my experience in the direction of the point could be zero. This may sound impossible but, according to modern geometry, this disappearance of separation without movement can occur in certain higher dimensional spaces and is akin to having two separate spots on a two dimensional sheet of newspaper and bringing them together by folding the sheet in the third dimension. Spots that are separated in two dimensions can be together in three. If such a phenomenon were to occur in my experience then the elements that are directed towards the apparent viewing point would have separate positions in space and time but be in contact with each other in a higher dimensional space.

This idea of the disappearance of separation may seem outrageous but it is consistent with some modern, physical hypotheses. For instance, experience could be a set of events loaded into a small, roughly spherical, volume of brain with the most recent events nearest to the centre, the events would be brought together by a geometrical effect analogous to the folding of a sheet of paper mentioned above. The disappearance of separation is also consistent with a projective geometry embedded in a five dimensional de Sitter space-time. This would be like ordinary four dimensional space-time but have one extra dimension to host the projection and zero net separations from an origin would be interpreted as a real lack of separation. The idea that the universe might involve de Sitter space-time is very common in physics and cosmology (see Silagadze 2007) and it would be curious to exclude such a possibility from neuroscience and philosophy of mind. When the alternative explanation in terms of lumps of stuff moving into an observation point is obviously wrong we should take the scientific approach of considering another possible hypothesis.

I am not saying that the apparent disappearance of separation discussed above is definitely explicable using higher dimensional spaces but I am pointing out that a disappearance of separation between the events in my experience is not unimaginable and might be described using physical theories (see Note 8).

The disappearance of separation described above means that my experience would not be “seen” by the apparent viewing point. If anything does the “seeing” it would be the whole interconnected geometrical entity that I call “experience” because, like the spots on the newspaper example above, the experience containing this page “now” would be directly connected at a point, and at no separation from, the experience containing this page “then”. In other words now can “see” then within the extended present (and possibly vice versa). As Aristotle put it, "the mind which is actively thinking is the objects which it thinks", there is no flow from experience to a centre point, experience is the centre point as well as distributed in space and time there being no separation between these locations in four dimensions.

This analysis shows that some concepts of geometry can be applied to the relationships within my experience and that an apparent observation point is not impossible.

Aristotle's regress

The way that two successive steps in a process can be both at the same instant in experience and separated in time answers Aristotle's regress because there is no need for an endless transfer of impressions from place to place: the form, motion, and other properties of mental objects within experience can all be present at the instant even though they may have required several processing steps over a period of time to be created. In answer to Aristotle's regress I can say that my experience has “both sight and its object” now. This agrees with Aristotle's own resolution of the problem: my mind is the objects that it thinks.

The Alexandrian theory of time, presentism and functionalism

A consequence of the description of conscious experience is that what Whitehead(1920) calls the “Alexandrian” theory of time (7), in which time is imagined as a simple succession of independent, instantaneous, spatially arranged events, should cease to be used in discussions of conscious experience, consciousness and mind. Alexandrian time is an everyday interpretation of time that roughly corresponds to the philosophical position known as “presentism”. My experience is nothing like the Alexandrian theory. It does not contain simple arrangements of things laid out in 3D but has a projective geometry of some kind and it does not contain independent successions of events but has events extended through an interval that are directed at a point in space and time.

The Alexandrian theory of time has been known to be false since the birth of Special Relativity Theory but it is still widely believed. If the Alexandrian theory is believed then conscious experience can only be successions of instantaneous and disconnected three dimensional spaces and a deep belief in the theory will result in the rejection of any descriptions of conscious experience that are in conflict with it. This then leads to the easy acceptance of proposals such as conscious experience being due to functions like those found in a digital computer (Putnam 1960, Dennett 1991), digital computers being successions of defined three dimensional states at each clock cycle. It also leads to reflexive models in which the mind results from no more than each three dimensional state acting on the next (Vygotsky (1925), Edelman (1993)). Such models embody a purely “intellectual rendering of experience” (Whitehead 1925) so they do not feel consistent with real experience and they give rise to an endless chain of relations (Harnad 1990). This approach also gives rise to the circular claim that conscious experience is a "judgment" of conscious experience (Dennett 1988).

The reason for the Alexandrian idea of space and time being so widely accepted in neuroscience is that most of our inferences and judgements and our pre-perceptual processing is performed using information processing in the cerebral cortex that occurs without conscious experience (Libet et al 1967). This means that a substantial fraction of what we call “awareness”, in the form of reports and inner speech, is derived from unconscious processes that may indeed be described using the analogies for physical processes that are available in the Alexandrian theory. As a result, in the same way as engineers can fashion new motor cars without having any knowledge of the real physics behind kinetic energy, neuroscientists can make progress on the aetiology and treatment of the brain without any insight into the nature of mind.

The reason why we have not yet understood the nature of conscious experience is that we have not yet understood the cosmos in sufficient depth. Most of the physical laws used in everyday scientific work are approximations for laws applying to quantum mechanical and relativistic phenomena such as kinetic energy and electromagnetism (Rindler 2001) and the path taken by moving objects involves the quantum interference between possible different paths available in both space and time (Ogborn and Taylor 2005). However, once this basic ontology of physical events is known it becomes clear that there are major problems that implicate conscious experience in physical theory. For instance, although Relativity Theory provides a physical ontology for kinetic energy it predicts a “block universe” in which all times exist and the universe is an eternally fixed four dimensional object. The fixed universe of Relativity Theory cannot explain change and this led Hermann Weyl (1918) to comment that reality is a "four-dimensional continuum which is neither 'time' nor 'space'. Only the consciousness that passes on in one portion of this world experiences the detached piece which comes to meet it and passes behind it, as history, that is, as a process that is going forward in time and takes place in space" (See Petkov (2006) for a modern update on Weyl's viewpoint). It is also the case that the state of the world described by quantum physics is heavily dependent on the state of the observer if that observer consists of passive ideas as described above (Zeh 1979) and that the "preferred basis" of quantum decoherence theory could be linked to conscious experience (Barrett 2005).

It can be seen that in the real world, with its non-Alexandrian ontology of physics, invoking “functions” to explain conscious experience leads to an examination of how functions operate. These functions operate as a result of relativistic and quantum physics which in turn require explanations that involve conscious experience. There is an endless loop or "infinite regress" inherent in functionalist explanations of mind in which conscious experience must be invoked to explain the functions that explain conscious experience. This regress applies to digital computers where proposing that the brain is a simple device like a digital computer leads to the question "how does a digital computer work?" which leads to the question "how do relativity and quantum theory work?" which leads to the problem of conscious observation. This circularity suggests it is time to rid neuroscience and philosophy of mind of “folk physics” such as functionalism.

The existence of time in conscious experience means that Alexandrian cosmology is an inappropriate foundation for analysing the mind. Should we be scientists and describe our experience before developing hypotheses to explain it or, like many philosophers, use a primitive cosmology to declare that conscious experience cannot exist?

Conclusion

My experience has a projective geometry with events extended through both time and space and directed at an instantaneous apparent observation point. This is inexplicable using mechanical functions but the relations between the events within my experience can probably be described using mathematics and physics. Conscious experience is likely to be susceptible to physical analysis. However, being largely epiphenomenal my experience cannot be simply integrated into the “environment” as a type of information processing and will require a more sophisticated analysis (see Note 5).

Notes

1.Aristotle states that: “By a 'sense' is meant what has the power of receiving into itself the sensible forms of things without the matter. This must be conceived of as taking place in the way in which a piece of wax takes on the impress of a signet-ring without the iron or gold;..” Book II.

2.On the subject of a regress Aristotle says: “Since it is through sense that we are aware that we are seeing or hearing, it must be either by sight that we are aware of seeing, or by some sense other than sight. But the sense that gives us this new sensation must perceive both sight and its object, viz. colour: so that either (1) there will be two senses both percipient of the same sensible object, or (2) the sense must be percipient of itself. Further, even if the sense which perceives sight were different from sight, we must either fall into an infinite regress, or we must somewhere assume a sense which is aware of itself.” Book III.

3.“In every case the mind which is actively thinking is the objects which it thinks. Whether it is possible for it while not existing separate from spatial conditions to think anything that is separate, or not, we must consider later.” Book III.

4.Descartes, Treatise on Man, writes: “Now among these figures, it is not those imprinted on the external sense organs, or on the internal surface of the brain, which should be taken to be ideas - but only those which are traced in the spirits on the surface of gland H (where the seat of the imagination and the 'common sense' is located). That is to say, it is only the latter figures which should be taken to be the forms or images which the rational soul united to this machine will consider directly when it imagines some object or perceives it by the senses.” Ideas are extended on the gland whereas the Res Cogitans has no extension, it is a point that views the ideas.

5.Zurek(2003) writes that: “The ‘higher functions’ of observers – e.g., consciousness, etc. – may be at present poorly understood, but it is safe to assume that they reflect physical processes in the information processing hardware of the brain. Hence, mental processes are in effect objective, as they leave an indelible imprint on the environment: The observer has no chance of perceiving either his memory, or any other macroscopic part of the Universe in some arbitrary superposition.” In other words, conscious experience has one form and does not consist of a superposition of states. As such conscious experience seems to be fairly unique because even after decoherence there is still a tiny quantum probability that any material object could also be elsewhere. If the part of the brain that hosts experience could be elsewhere or have several superposed forms then what would be the probability of observation being double or superposed? We know that the probability of an external observer seeing any significant superposition of brain states might be vanishingly small but why would our observation be constrained to that which has the highest probability? Where do the other possible forms of our observation go to when we are the only ones looking? Unless there is some property of the form of our observation itself that makes it the only possible observation then Aristotle's regress returns and we are left imagining an internal observer who observes our observation and finds it to be in the "most probable" state.

6.Kant(1781) writes that “Space is a necessary a priori representation, which underlies all outer intuitions. We can never represent to ourselves the absence of space, though we can quite well think it as empty of objects. It must therefore be regarded as the condition of the possibility of appearances, and not as a determination dependent upon them. It is an a priori representation, which necessarily underlies outer appearances. 3. The apodeictic certainty of all geometrical propositions and the possibility of their a priori construction is grounded in this a priori necessity of space. ........." and on the subject of time writes: ....“Time is not an empirical concept that has been derived from any experience. For neither coexistence nor succession would ever come within our perception, if the representation of time were not presupposed as underlying them a priori.”

7.Whitehead has strong views on the prevailing models of time in philosophy: "The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries accepted as their natural philosophy a certain circle of concepts which were as rigid and definite as those of the philosophy of the middle ages, and were accepted with as little critical research. I will call this natural philosophy 'materialism.' ..... It can be summarised as the belief that nature is an aggregate of material and that this material exists in some sense at each successive member of a one-dimensional series of extensionless instants of time. ..... This theory is a purely intellectual rendering of experience which has had the luck to get itself formulated at the dawn of scientific thought. It has dominated the language and the imagination of science since science flourished in Alexandria, with the result that it is now hardly possible to speak without appearing to assume its immediate obviousness." (Whitehead 1920).

8. If time exists then Minkowski's equation for separations in space-time could be interpreted as describing real separations. Minkowski's equation is:

ds2 = dr2 - (cdt)2

Where "dr" is spatial separation, "c" is the speed of light and "dt" is temporal separation. Notice the negative sign which results in "ds", the net separation, being zero when dr equals cdt. Of course, this analysis only applies if dimensional time exists and the events described by the equation are still separated in space and in time even though, in the direction of ds in spacetime they have zero net separation. The separation, ds, is actually the path of a photon and if you went down this path with a clock and a ruler you would find that it has no length and it takes no time to traverse the path.

Bibliography

Aristotle. On the Soul.

Berkeley, G. (1710). A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge.

Barrett, J.A.(2005) The preferred basis problem and the quantum mechanics of everything. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 56, 2, June 2005 , pp. 199-220(22)

Blackmore, S. (2002) There is no stream of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, Volume 9, number 5-6

Clarke, C.J.S. (1995). The nonlocality of mind. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2:231-40.

Clay, E.R. Quoted in Principles of Psychology by William James. First published 1890. Published 1950 Courier Dover Publications.

Corti, W.R. (1976) The Philosophy of William James. Meiner Verlag.

Cutting, J.E. & Vishton, P.M. (1995) Perceiving layout and knowing distances: The integration, relative potency, and contextual use of different information about depth. In W. Epstein & S. Rogers (eds.) Handbook of perception and cognition, Vol 5; Perception of space and motion. (pp. 69-117). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Daniel C Dennett. (1988). Quining Qualia. in A. Marcel and E. Bisiach, eds, Consciousness in Modern Science, Oxford University Press 1988. Reprinted in W. Lycan, ed., Mind and Cognition: A Reader, MIT Press, 1990, A. Goldman, ed. Readings in Philosophy and Cognitive Science, MIT Press, 1993.

Daniel C Dennett. (1991). Consciousness Explained. Little, Brown & Co. USA.

Descartes, R. (1641). Meditations on First Philosophy.

Descartes, R. (1664) Treatise on Man. Translated by John Cottingham, et al. The

Philosophical Writings of Descartes, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1985) 99-108.

Edelman, G.M. (1993). Bright Air, Brilliant Fire: On the Matter of the Mind. New York.

Gombrich, E. (1964) Moment and Movement in Art, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes XXVII, 293-306

Gunaratana, H. (1988). The Buddhist Publication Society. Especially: The Jhanas In Theravada Buddhist Meditation. The Wheel Publication No. 351/353. 1988 Buddhist Publication Society

Harnad, S. (1990) The Symbol Grounding Problem. Physica D 42: 335-346.

Kant, I. (1781) Critique of Pure Reason. Trans. Norman Kemp Smith with preface by Howard Caygill. Pub: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kornhuber HH, Deecke L: Hirnpotentialänderungen beim Menschen vor und nach Willkürbewegungen, dargestellt mit Magnetbandspeicherung und Rückwärtsanalyse. Pflügers Arch. ges. Physiol. 281 (1964) 52.

Leibniz, G (1695). The New System.

Le Morvan, P. (2004). Arguments against direct realism and how to counter them, American Philosophical Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2004): 221-234.

Le Poidevin (2000). The Experience and Perception of Time. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu//archives/spr2001/entries/time-experience

Libet, B., Alberts, E.W., Wright, E. W., Feinstein, B.(1967). Responses of Human Somatosensory Cortex to Stimuli Below Threshold for Conscious Sensation. Science 158, 1597-1600.

Lindner, F., Schaetzel, F.G., Walther, H., Baltuska, A., Goulielmakis, E., Krausz, F., Milosevic, D.B., Bauer, D., Becker, W., and Paulus, G.G.. (2005) Attosecond double-slit experiment. Phys.Rev.Lett. 95,040401 (2005)

McTaggart, J. (1908). The Unreality of Time. Mind: A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy 17 (1908): 456-473.

Ogborn, K. and Taylor, E.F. (2005). Quantum Physics explains Newton's laws

of motion. Physics education. 40(1) 26-34.

Petkov, V. (2006). Is There an Alternative to the Block Universe View?, in: D. Dieks and M. Redei (eds.), The Ontology of Spacetime. Series on the Philosophy and Foundations of Physics (Elsevier, Amsterdam)

Putnam, H (1960). Minds and Machines. Dimensions of Mind, ed. Sidney Hook. New York University Press.

Rea, M. C., (2003). Four Dimensionalism. The Oxford Handbook for Metaphysics. Oxford Univ. Press.

Reid, T. (1764). An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense.

Edited by Brookes, Derek. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997

Rindler, W. (2001): Relativity: Special, General and Cosmological. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York

Ryle, G. (1949) The Concept of Mind. Penguin Classics. Original Hutchinson edition republished by Penguin Books (2000), London, with an introduction by Daniel C. Dennett.

Silagadze, Z.K. (2007). Relativity without tears. eprint arXiv:0708.0929

Soon, C.S., Brass, M., Heinze, H-J. and Haynes, J-D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience 11, 543 - 545 (2008)

Vygotsky, L.S.(1925) Consciousness as a problem in the psychology of behavior. Undiscovered Vygotsky: Etudes on the pre-history of cultural-historical psychology (European Studies in the History of Science and Ideas. Vol. 8), pp. 251-281. Peter Lang Publishing. http://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/1925/consciousness.htm

Weyl, H. (1918). Space Time Matter. Dover Edition 1952, p.217.

Whitehead, A.N. (1920) The concept of nature. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1920.

Whitehead, A.N. (1925). Science and the Modern World (1925). 1997 Free Press (Simon & Schuster)

Zeh, H. D. (1979). Quantum Theory and Time Asymmetry. Foundations of Physics, Vol 9, pp 803-818 (1979) http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0307013

Zurek, W.H. (2003). Decoherence, einselection and the quantum origins of the

classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 715 (2003)

I thought this was very good and thought-provoking.

ReplyDeleteYour description of the problem was helpful: how do contents of experience which are extended in space and time seem to be directed toward an experiencing point with no separation? It seems the contents are bound to the point in some not-conventionally-geometric fashion. “Experience” necessarily includes both the contents themselves as well as the apparent viewing point with no separation.

I agree that the solution lies in the nature of the cosmos. You touch on some ideas, including the possibility of higher-dimensional space. I’m thinking the solution could come via an idea contained in a recent class of QG theories. The idea is that space-time geometry as we know it now (described by GR) emerges from an underlying microscopic network of quantum events. The flow of experience is grounded in the fundamental level, not the emergent level, and this is the source of the discontinuity between experience and conventional geometrical intuitions.

Interesting comments.

ReplyDeleteAt the empirical level it is enough that there could be a physical theory to account for the apparent geometry of conscious experience. If physics, either through a fundamental spacetime or through an emergent spacetime, does not forbid our experience then it is reasonable to extend the empirical description of experience in the hope that, one day, physics will catch up.

You wrote:

ReplyDelete"My experience has a projective geometry with events extended through both time and space and directed at an instantaneous apparent observation point. This is inexplicable using mechanical functions but the relations between the events within my experience can probably be described using mathematics and physics."

Can neuronal brain mechanisms explain your experience? See the function of clock rings and recall rings in conjunction with synaptic matrices and retinoid mechanisms in *The Cognitive Brain*, Ch. 5 " Accessory Circuits", pp. 93-97. Here:

http://www.people.umass.edu/trehub/thecognitivebrain/chapter5.pdf

If evoked autaptic cell images (visual/auditory) were were to decay over epochs of seconds, then your experience of the extended present would have the "saddle-back" contour you mention. Mathematics may be suited to *describe* your experience, but a biological mechanism is needed to provide a *causal* explanation of your experience.

Hi Guys,

ReplyDeleteThing is, like you I've been doing some research and thinking.

The general direction of mankind is one of trying to understand who he really is; he will not be content until he gets there. That is, the point where he understands all that it is possible to understand sometimes known as the grand theory of everything, if you like. If something is not knowable and it is known that it is not physically possible to know it then it might be possible to legitimately exclude such an item from such a Grand Theory of Everything.

One can tell one is approaching such a theory when, as one gets closer, the various candidates for inclusion start to appear in there not by deliberate inclusion, but just because that’s their natural place and they are there whether we want them to be or not.

My background is one of an electronic systems design engineer. I used to design computers and radars, but given some time I felt compelled to develop my knowledge of quantum mechanics. It is a specialist field and I can see many people thinking: sounds nice for you, but I’m going to have to leave here I’m afraid. My point here is that unless that person is willing to get to grips with at least some of the subject he will never understand ‘everything’ and constantly continue his consciousness research down the insular and specialist field of consciousness studies. Likewise the physicist will continue down his narrow specialist field.

With regards to consciousness and Alex Green’s deliberations I think I can bring some revolutionary information which changed my life when I understood it and which I think will change the scientific world as well. It is something which incorporates physics and consciousness studies and at the same time highlights a clear distinct boundary over which science knows it has to leave off. I am burdened because I’m on my own here and I don’t really know what to do with this knowledge, though I can say that I intuitively know the direction of mankind’s knowledge and where it will end up. It’s rather similar to how Einstein knew he was right when he said "God does not play dice" and yet was unable to prove it (he was right by the way). I yearn to present the knowledge but to do it with any legitimacy it has to be presented as a whole. Although the equations are beautiful in their simplicity, to the lay man they are difficult to understand, their presentation needs careful consideration and such presentation could be quite big.

I don’t know how to present such knowledge which seems to go a long way down the path of unification. It truly deserves a web site of it’s own yet it relies heavily on the work of specialists in each of the fields. I cannot present a coherent argument in the small space I have here, yet I have to present it somewhere. Is there anyone who can spend some time listening to me with the understanding that this may lead to the work involved in building a web site? On the plus side the magnitude and significance of it all would probably lead to some form of book or film or documentary or… .

Hi Guys,

ReplyDeleteThing is, like you I've been doing some research and thinking.

The direction of mankind is one of trying to understand who he really is; he will not be content until he gets there. That is, the point where he understands all that it is possible to understand. If something is not knowable and it is known that it is not physically possible to know it then it might be possible to legitimately exclude such an item from such a Grand Theory of Everything.

One can tell one is approaching such a theory when, as one gets closer, the various candidates for inclusion start to appear in there not by deliberate inclusion, but because that’s their natural place and they are there whether we want them to be or not.

My background is one of an electronic systems design engineer. I used to design computers and radars, but given some time I felt compelled to develop my knowledge of quantum mechanics. It is a specialist field and I can see many people thinking: sounds nice for you, but I’m going to have to leave here I’m afraid. My point here is that unless that person is willing to get to grips with at least some of the subject he will never understand ‘everything’ and constantly continue his consciousness research down the insular and specialist field of consciousness studies. Likewise the physicist will continue down his narrow specialist field.

With regards to consciousness and Alex Green’s deliberations I think I can bring some revolutionary information which changed my life when I understood it and which I think will change the scientific world as well. It is something which incorporates physics and consciousness studies and at the same time highlights a clear distinct boundary over which science knows it has to leave off. I am burdened because I’m on my own here and I don’t really know what to do with this knowledge, though I can say that I intuitively know the direction of mankind’s knowledge and where it will end up. It’s rather similar to how Einstein knew he was right when he said "God does not play dice" and yet was unable to prove it (he was right by the way). I yearn to present the knowledge but to do it with any legitimacy it has to be presented as a whole. Although the equations are beautiful in their simplicity, to the lay man they are difficult to understand, their presentation needs careful consideration and such presentation could be quite big.

cont'd

I don’t know how to present such knowledge which seems to go a long way down the path of unification. It truly deserves a web site of it’s own yet it relies heavily on the work of specialists in each of the fields. I cannot present a coherent argument in the small space I have here, yet I have to present it somewhere. Is there anyone who can spend some time listening to me with the understanding that this may lead to the work involved in building a web site? On the plus side the magnitude and significance of it all would probably lead to some form of book or film or documentary or… .

ReplyDeleteHi Carlb. See 't Hooft's guide to becoming a theoretical physicist.

ReplyDeleteIf I have a physical theory then I should have physical predictions. If I am an outsider I should have physical predictions that are really easily testable. This is why I have tried to confine this site to observations rather than theories - I only point out that a physical theory is possible. Alex Green has proposed a few tests but I have not produced any testable theory as yet.

I see that you have a blog page. Why not describe the test(s) that will prove your theory and the theoretical reasoning behind those tests on the page and link to it here.

Hi Carlb. Try reading 't Hooft's guide to becoming a theoretical physicist.

ReplyDeleteIf I were you I would use your blog page to present the details of one or two experiments that can easily be performed in the lab and which will test your theory, along with the details of the theory that support the experiments.

Maybe I go too far on this website. It probably gives the impression that I support a particular theory of conscious experience - I don't, I just want to show that our observations and experience are not incompatible with the possibility of a physical theory.

Thanks Thoughts. But the thing is, my contribution is seeing the connections and bringing together the different elements of the picture. The theory quantum theory I talk of is already out there. It was thought of by a professor of physics at a well known university. It has experimental evidence from all the quantum experiments to-date to back it up. It derives gravity rather than percepualises it as an invisible string (i.e. spooky forces acting at a distance). It explains the answer to Mach's inertia paradox. It answers Einstein's heart-felt desire to describe the field which surrounds the tiniest particle and gives rise to the forces and communications that are known to exist and have been measured countless times but all with no explanation as to how they happen.

ReplyDeleteI know you mean good, and really thanks for the advice, but you see that's my problem; anyone working outside the field isn't aware of the issues in the field and therefore can't see the brilliance of the answers.

I don't want to become a theoretical physicist, I leave that to the experts.

I repeat my request and am willing to describe the (qm) issues to anyone interested, provided they are able to understand and they understand the consequences as I described above.

Perhaps I should have emphasised above that I have seen and understood a quantum physical theory which matches the observations Alex talks about.

ReplyDeleteI look for a partner to understand both aspects and can help communicate the resultant picture to the world.

I found the discussion of the geometry of temporal experience absolutely fascinating. The thing I always try to keep in mind is simply how little of the information processed by the brain makes its way to experience. Given this, the way experiential time contradicts physical time probably means that the former is a kluge of some sort, a forced illusion. Since this is the default, I think you need to either provide some argument against it, or provide some argument for treating your phenomenological descriptions as primary.

ReplyDeleteI actually think what we call the 'now' is simply the empty frame of our 'temporal field.' The same way that visual attention has a focus, fringe, and margin (where visual awareness ends), so does our 'temporal attention.' The now (and all its peculiar phenomenological properties), I think, is simply an artifact of our temporal margin, the point at which temporal awareness ends. Check out http://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2011/01/27/t-zero/ if you're interested in a more detailed account. I'd be interested to hear your take!

The real problem here seems to me to be "space" rather than time. No one has ever seriously proposed that our experience is less than a dot ".". The proposal that there is nothing simultaneously in experience is equivalent to the proposal that experience does not exist (or is zero dimensional which amounts to the same theory).

ReplyDeleteIf there are simultaneous events in experience then experience is a space. But notice the "simultaneous". We could define "simultaneous" as being identical clock readings on each event but that does not capture our phenomenal simultaneity. Phenomenal experience does not involve visiting each point event and taking its time on a clock. Phenomenal experience is having events at an observation point.

In mathematical terms the events on the surface of the sphere:

r^2 = x^2 + y^2 + z^2

are simultaneous at a centre point if:

0 = r^2 - (vt)^2

where vt is the product of the velocity of the event towards the point and t is the time taken to move from the sphere to the point. But this could not be happening in the brain, stuff would just pile up in a point!

These events that we are discussing are laid out in the space of phenomenal experience and are one sided, We see "b", not "d" - which is "b" from the rear view. Phenomenal events are actually vectors directed at a point. The phenomenal events do not exist by themselves as 3D entities. So, there is indeed phenomenal space, which is the existence of more than one event, and the events are not 3D objects.

Suppose they are 4D objects. In this case:

0 = r^2 - (ct)^2

where t is now a negative dimension that causes the disappearance of space in the direction of the vectors.

Alex Green summarised this nicely in her paper:

Alex Green's original paper

Note: physical simultaneity depends upon the velocity of an observation point. See Special Relativity

I'm not sure I understand. Experience resides in about 1200 ccs of brain tissue. Why is any other kind of space required?

ReplyDeleteNo other kind of space-time is required. But you cannot model experience using space without time and you cannot model experience using a model of space and time where each instant is a separate space from the next. See Materialists should read this first.

ReplyDeleteI'm not a materialist. What you critique as 'Alexandrian time' I've critiqued as Aristotelian time for decades (I was a Heideggerean for some time - ah, youth!).

ReplyDeleteExperience escapes description according to what he calls the 'metaphysics of presence,' where time is conceived of as points rather than - he doesn't use 'space' like you do, but avails himself of other concepts with spatial connotations, such as 'clearing.'

My initial point was that: "The thing I always try to keep in mind is simply how little of the information processed by the brain makes its way to experience. Given this, the way experiential time contradicts physical time probably means that the former is a kluge of some sort, a forced illusion. Since this is the default, I think you need to either provide some argument against it, or provide some argument for treating your phenomenological descriptions as primary."

To which you replied that experience has to be 'spatial'in some sense.

Whereupon I asked why the skull wasn't space enough.

I feel as though we have simply come back to my original question: Where is your argument for why we should treat phenomenological descriptions as primary, rather than a forced illusion.

In a sense I'm doing the same thing you are: providing an account for why experience has the (decidedly non-Aristotelian) temporal structure it does. But where I treat it as a structurally mandated illusion (for the reasons cited above), you treat it as primary.

I'm just wondering why.

Why should we treat phenomenological descriptions as primary? Firstly, we would need a good reason not to do so because they are prima facie primary. Secondly, if time exists there is no time for further processing between a present experience and itself. (Although we can experience processes extended over time, as described in the article above.)

ReplyDeleteIf we take processing outside of experience then it is not primary in experience.

I would regard illusion as experience and whenever I have seen illusions they have been spatially and temporally arranged and primary.(See The spatial modes of experience).

Occam's razor sure isn't in any of your guy's vocabularies. Extra dimensions and 50-cent words are no more convincing than simple evolutionary physicality. Possibly something along the lines of Philip Clapson's Brain-sign Theory.

ReplyDelete"Extra dimensions and 50-cent words" which words caused you difficulty?

ReplyDeleteAll thanks to Mr Anderson for helping with my profits and making my fifth withdrawal possible. I'm here to share an amazing life changing opportunity with you. its called Bitcoin / Forex trading options. it is a highly lucrative business which can earn you as much as $2,570 in a week from an initial investment of just $200. I am living proof of this great business opportunity. If anyone is interested in trading on bitcoin or any cryptocurrency and want a successful trade without losing notify Mr Anderson now.Whatsapp: (+447883246472 )

ReplyDeleteEmail: tdameritrade077@gmail.com